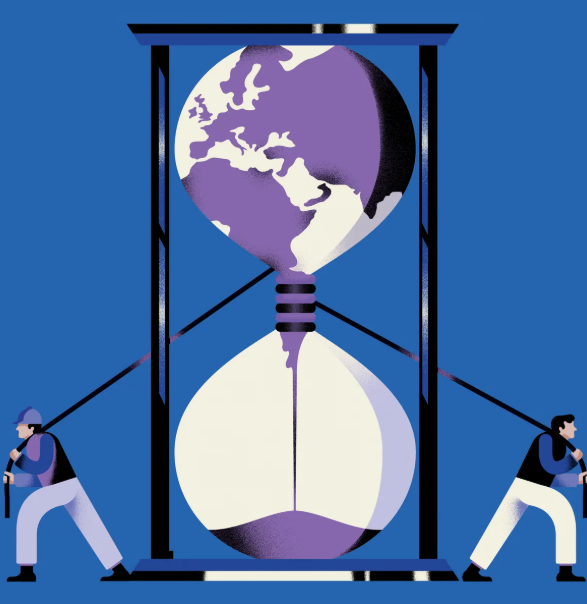

How Climate Change is Shaping Global Economies and Political Stability

Climate change has evolved from being seen as an environmental concern to a major force that impacts global economies and political stability. Its effects reach far beyond the environment, affecting agriculture, supply chains, job markets, and international relations. As nations grapple with rising costs, shifting job markets, and increasing infrastructure vulnerabilities, industries are being forced to adapt or face collapse. The interconnectedness of today’s world exposes the fragility of systems that once seemed stable, demanding a major overhaul in how societies approach economic and political resilience.

On the political front, climate change is often referred to as a “threat multiplier,” as it exacerbates existing vulnerabilities and creates new challenges. Competition over resources, migration pressures, and the deepening of social inequalities all fuel political instability. Governments around the world are struggling to address these issues in ways that are equitable and sustainable. As climate change becomes the defining issue of our time, the need for effective and forward-thinking policies has never been greater.

Climate Change as a Disruptive Global Force

For decades, climate change was seen primarily as an environmental issue, with a focus on melting ice caps and endangered species. However, the consequences of climate change are now understood as much broader, with the potential to disrupt everything from food prices to international trade. Economists, policymakers, and military leaders alike are now acknowledging climate change as a “threat multiplier,” a force that amplifies existing weaknesses in political and economic systems.

Climate change is not just about extreme weather—it reshapes global economic and political landscapes, driving up costs, disrupting trade, and testing the resilience of political institutions. It is causing billions of dollars in damages, displacing millions of people, and destabilizing already fragile regions. The challenge is no longer just about reducing carbon emissions; it is about addressing the economic and political fallout of an increasingly unstable planet.

Economic Disruptions Caused by Climate Change

The agricultural sector is perhaps the most directly impacted by climate change. Changes in weather patterns—such as erratic rainfall, prolonged droughts, and floods—are disrupting traditional farming practices. In regions like Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, where agriculture forms the backbone of economies, crop yields for staples like rice, maize, and wheat are on the decline due to rising temperatures and water scarcity.

Even in developed countries, farmers are adjusting to new realities. For instance, California’s Central Valley, once one of the world’s most productive agricultural regions, is now facing persistent water shortages. Meanwhile, shifting climate zones are pushing agricultural production into new territories, such as vineyards expanding into southern England or soybeans being cultivated in Canada. These transitions, while offering new opportunities, come with significant financial, environmental, and social costs.

The impacts of climate change are also felt in the insurance sector. Extreme weather events—hurricanes, wildfires, and floods—are becoming more frequent, resulting in enormous financial losses for both public and private entities. The World Bank estimates that climate-related disasters are costing cities over $300 billion annually. As sea levels rise, cities like Miami and Jakarta are investing heavily in coastal defenses and infrastructure upgrades just to remain livable.

The global economy also faces disruptions in supply chains. The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how vulnerable interconnected systems can be, and climate change adds another layer of risk. For example, record-low water levels in the Rhine River in Germany have restricted the flow of goods, while droughts have caused delays at the Panama Canal, raising shipping costs and further inflating consumer prices.

Job markets are also being reshaped. Climate-sensitive industries such as agriculture, fishing, and tourism are facing volatility, with job security and income levels fluctuating as a result. Small island nations dependent on tourism are seeing a decline as coral reefs and marine ecosystems suffer from rising temperatures. Similarly, rural communities are being displaced as farmlands turn to desert, leading to overcrowded cities and social tensions.

However, there is a silver lining. The green economy is booming, with the potential for millions of new jobs in renewable energy, sustainable construction, and climate adaptation. The International Labour Organization predicts that transitioning to a low-carbon economy could create 24 million jobs by 2030, provided the right policies are implemented. Still, this shift requires significant investment in education and re-skilling, which could deepen inequality if not managed properly.

Political Strain and Governance Challenges

Climate change is also a political challenge, creating new stress points within and between nations. As resources such as freshwater and arable land become scarcer, competition for these essential commodities intensifies. In many parts of the world, access to water is already a contentious issue, with rivers like the Nile and the Mekong facing increasingly unpredictable flows. In regions like South Asia, the melting of glaciers in the Himalayas threatens to disrupt the water supply for millions, potentially leading to tensions between neighboring countries.

Within countries, competition for resources is also escalating. In the United States, for instance, disputes over water rights in the Colorado River have prompted federal intervention, highlighting the growing strain on governance systems. These disputes are not just bureaucratic—they are indicative of the pressures that climate scarcity will place on political systems, especially in countries already grappling with inequality and polarization.

Climate migration is another emerging political issue. As sea levels rise and droughts intensify, people are being forced to leave their homes. In Bangladesh, for example, sea-level rise is projected to displace up to 17% of the population by 2050. In Central America, recurring crop failures are driving migration northward. These movements strain urban centers and neighboring countries, leading to competition for jobs, housing, and public services—conditions ripe for political instability and the rise of nationalist policies.

Governments are increasingly caught between the urgent need for climate action and the limits of their political capital. Poorly managed climate policies, such as carbon taxes that provoke public backlash or failed transition plans, can ignite social unrest. The costs of adaptation are often borne unevenly, with marginalized communities, who are least responsible for climate change, receiving the fewest resources to cope with its effects. This disparity fuels resentment and can lead to political instability.

The Uneven Approach to Adaptation

Adaptation to climate change is not happening equally across the globe. Wealthy nations have the resources to invest in resilience—building sea walls, retrofitting infrastructure, and developing green technologies. On the other hand, developing countries often lack the financial means to protect themselves, relying on insufficient international aid or loans that increase their debt burdens. This adaptation gap is deepening, leaving the most vulnerable nations least equipped to face the challenges posed by climate change.

The 2022 floods in Pakistan, which submerged a third of the country and displaced millions, starkly highlighted the inequities of adaptation. While the disaster was driven by climate factors largely beyond Pakistan’s control, its recovery was hindered by economic fragility and a lack of international support. This unequal ability to adapt not only worsens global inequalities but also destabilizes regions that are already struggling to cope with the pressures of climate change.

Corporations, too, vary in their preparedness. Some businesses are integrating climate risk into their strategies, investing in supply chain resilience and decarbonization efforts. Others, however, are still treating climate change as a compliance issue rather than a systemic risk, leaving them vulnerable to future disruptions.

Governments are similarly divided in their approach. Cities like Rotterdam and Singapore have become global leaders in resilience planning, while others lack even basic disaster preparedness. When adaptation efforts are reactive rather than proactive, the costs are higher, and recovery is slower.

Key Takeaways

Confronting the reality of climate change can feel overwhelming, but it is possible to move forward with optimism. Younger generations, such as Millennials and Gen Z, are deeply aware of the issue and motivated to take action. Climate change is no longer a distant threat—it is a present reality that is reshaping economies, borders, and political systems. The transition to a climate-resilient future is already underway, though it is happening unevenly across regions and sectors.

The challenge now is managing this transition effectively. Can we create systems that are both equitable and efficient? Will the benefits of adaptation be shared widely, or will they be concentrated in the hands of a few? These are the questions that will define the future. The choices we make today will determine the kind of world we leave behind for future generations.

English

English